- Job title Aero-performance Engineer

- Organisation Sahara Force India Formula One Team

- CourseDefence and Security PhD 2017, Motorsport Engineering and Management MSc 2013

In recognition of the calibre of his PhD, his drive and contribution to the University, we congratulate Luke Roberts, winner of the 2018 Lord Kings Norton Medal.

Named after Lord Kings Norton, Cranfield’s first Chancellor, this medal is the only prize awarded across all doctorate students at the University. This is only the second time it has been awarded to two students in the same year.

“I always wanted to do a PhD, but I didn’t expect to be able to find the PhD that I wanted. This project was quite perfect. Winning this award is recognition that my PhD was of good quality.”

“I've always been very competitive and racing ticks all the boxes for me. I knew I wanted to go into engineering since I was quite young. My father was a software developer, so I had always been around technology. Engineering seemed quite clearly the way forward.

“I knew what I wanted to do as a job and where I wanted to go, so I didn't expect to find a PhD that was right for my career, but always wanted to do one.

“I did my PhD in low-speed aerodynamics, the title is “Boundary-layer transition on wings in ground effect”. At Force India I’m an Aero-performance Engineer.

“A racing car travels at quite a lot of different speeds at it goes round the track. That affects the aerodynamics quite heavily. The bit I’m most interested in is where the air is very close to the surface, which is what we call the boundary layer. Broadly speaking, as the car speeds up, you tend to go from very smooth flow, which we call laminar, to chaotic flow, which we call turbulent. My research was about where that transition occurs and how it affects the wing, then secondly how well can it be modelled in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD).

“Most CFD packages assume turbulent flow all the time, which isn’t accurate for low-speed flows. There are newer models that include this smooth laminar effect and I was evaluating how good those models are to this specific application.

“The racing car environment is a lot more extreme than airplanes: they produce a lot more load and there are very large pressure changes, and it hasn’t really been looked in that environment.”

Career

“You don’t have to have a PhD to do my job, but it’s certainly given me a good basis to build from. My role here is a halfway step between the race engineering side and the design aerodynamic side. Acting as a link, it’s good to have knowledge in both areas.

“What I enjoy most is that every week is something different. I get to go to some of the tests and have to be in for all races as I’m remote support from the office.

“Part of my job is analysing the data coming from the car and every week we’re at a different track and the cars are running a different programme. We have different parts on the car, so there's never one week the same and you have to adapt yourself to a new challenge each week.

“My goal now is to progress up, get more responsibility and may be a broader reach in my job role”

The best bits

“During my PhD I went to work for multiple race teams, first as a performance engineer and then as a race engineer. That is quite important to learn how the aerodynamics effect the race car itself.

“I did a few years with F3, the most exciting part was Macau Grand Prix. We qualified second on the grid, it was looking quite good. But three corners and he got knocked out of the race and the weekend was over. Still, it was definitely the best experience.

“As the performance engineer I was at the back of the garage looking through data trying to find ways to improve performance of both the car and driver. The race engineer was in the driver’s ear and I was in the race engineer’s ear. Its high pressure, with time constraints, you’ve got to make the decision and get on with it – and that’s what I like about it.

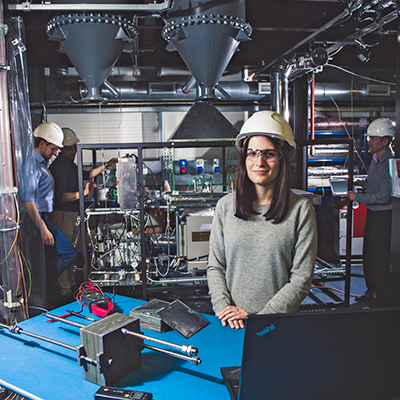

“The wind tunnel at Shrivenham is very good – it’s the old Reynard wind tunnel. They used to develop racing cars there and have quite a lot of racing car models. The design of that wind tunnel is similar to the one at Reynard Park, which is Mercedes’ and also the one at Toro Rosso in Bicester. There are a lot of similarities between those tunnels, which is very useful for my PhD project.

“It's not commercially used as much as the Bedford site, so I got a lot more time in it: I would run experiments in the Shrivenham tunnel for months.

“I went to a couple of conferences – one in France, one in Britain, one in America, so I got to present my work quite widely. I was lucky enough to meet a lot of the aerospace authors that I’d been citing in my work too.

“I managed to produce quite a lot of journal articles out of my research. I now have seven publications, six journal paperss and four conference papers. That was my aim from the start - knowing that if my research had been evaluated by my peers in academia and published then, when I got to the viva I knew I would be okay. It also means that my research is more likely to be used by industry.

“There were a few other research students in my office with me and one of the guys was more CFD based than I am, (I was a lot more experimental), so it was really helpful to bounce ideas off each other.

“Winning this award is recognition that my PhD was of good quality. When you do a PhD you hole yourself up a little bit, especially when writing up. And you end up with doubts – is it as good as it could be? Is it the best I can do? And winning the medal shows me that it was good.”

Advice

“I think you’ve got to have determination more than anything. A PhD is a marathon not a sprint, and there are a lot of challenging times, but it is worth it by the end. You have to have the determination to really do it.

“Don’t worry about what happens on one day. If you don't get the results you want, or the data isn’t what you expect, or you're a bit behind, you don't need to worry all day or kill yourself in one day trying to get it right. Pace yourself.”